Where do you begin a history of electronic music and the synthesizer? The popular and somewhat easy view is that the two are entwined, that electronic music started with the invention of the synthesiser and its use in the 60s and 70s. But actually the synthetic manipulation of sound, and the machines that did it can be traced back further. Much further.

In fact, both experimentation with sound and some weird and wonderful sonic manipulators go back hundreds of years. OK, the fun really started when people started recording and releasing the results a few decades back – not to mention making accurate records of the machines that they created – but before we get to the 60s, there’s a couple of hundred years to cover (albeit briefly), including some claims to discuss, some to dismiss and some others that are just, well, shocking… in all the wrong ways.

The start?

Taking things way back, you can make the case that the beautiful-sounding Golden Dionysis was very possibly the first electrical musical instrument. It was ‘built’ by the Czech electrical researcher Václav Prokop Diviš in 1748, who claimed to be able to recreate string and wind sounds with it.

You’ll note that we say ‘claimed’ and ‘very possibly’, so, like we say, it might be better to move to firmer historic ground, over a century later when, at the very least, some of the claims were justified and recorded. (We’ll also note that other accounts of the time state that the instrument gave its users electric shocks… so we’re not exactly talking plug ‘n’ play!)

For this, we travel forward to the end of the late 19th century and Matthaüs Hipp’s Electromechanic Piano, which triggered sound by way of activating electric magnets with a keyboard. Even better records exist about the Telharmonium, developed at the same time by Thaddeus Cahill, an instrument not only capable of altering or indeed synthesising sound, but spreading it across the newly created phone network. (This instrument can therefore not only claim to be the first synth but also the first to use an early form of the internet. Sort of.)

Meanwhile, in the late 19th century, Elisha Gray is also noted as (almost) accidentally inventing the synth oscillator while developing a telephone prototype in the late 19th century. But if you think it’s a complex history in this era, just wait until the next century…

20th century vision

Things get even more complex in the early 20th century, with a range of instruments that could and would lay claim to chunks of electronic music history, not least the electric organ and another couple of standout devices, notably the Helmholtz Sound Synthesiser and Theremin.

The Sound Synthesiser was not only the first instrument to claim the ‘synth’ name, but used overtones and even basic filtering in the creation of sounds – some of the important sonic ingredients still used today. So we now seem to have arrived at the dawn of electronic music as the artificial manipulation of sound – arguably the very definition of the genre – becomes a reality.

As we progress through the century, there was Ivor Darreg who, in the 1930s and 40s, designed instruments called the Electronic Keyboard Oboe and Electric Keyboard Drum, which could lay claim to being the first electric instruments specifically intended for music.

READ MOREWhat is analogue synthesis? The ultimate beginner's guide

And as we dig deeper, other important instruments included the 1930s Trautonium, made by Freidrich Trautwein, and then enhanced into the post-Second World War Mixturtrautonium by Oskar Sala. Using what was called a ‘Sub-harmonic’ technique of sound creation, these allowed you to mix, match and modulate signals with controls like envelope shapers and frequency shifters which would later become common in subtractive synths.

In the 1950s, two opposing currents prevailed: the experimental, highly artistic musique concrète movement helped take electronic music in new directions, creating whole new genres of music almost unwittingly.

Meanwhile, at the ‘establishment’ end of things, RCA built a room full of electronics – in part for arguably shady war-time reasons – but in doing so, eventually came up with something called the Electronic Music Synthesizer Mk1.

This ended up being almost sequencer-like in its ability – you could define note timbre, volumes, envelopes and so on – but it was actually intended to produce a formula for hits, a kind of robot Stock Aitken & Waterman of its time.

Luckily, this concept was dropped, but the idea of creating sound electronically was leapt upon and a Mk2 version was developed at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, and was used to help create music like Charles Wuorinen’s Time’s Encomium, which eventually won the Pulitzer Prize for music.

The Theremin

The 1920s Theremin is a unique device in electronic music making, not so much used to create sounds, but perform them. OK, its eerie tone is a bit of a one-off, but it has claimed its part in music history – particularly in early sci-fi and Beach Boys tunes – largely down to this rather atmospheric tone and the way it is produced.

A performer can alter the pitch and volume of the sound merely by moving their hand up and down and further away from the device. The story behind its invention and popularity is like something out of a film, and deserves its own book.

As fascinating as it is, though, this story runs on a different course to that of the synth (almost, in fact, in a parallel dimension), although, like the synth, you can now create the sound of the Theremin in software and there are also up-to-date hardware versions, notably the Moog Theremini.

Musique concrète

The concept of musique concrète is an important one in the history of electronic music production, not least because it got people thinking and composing along very different paths compared to using traditional notes, timbres and scales.

\Initially popularised by Pierre Schaeffer in the mid-20th century, whose work would lead to the formation of the Groupe de Recherches de Musique Concrète and Groupe de Recherches Musicales, it would attract the likes of Pierre Boulez, Pierre Henry, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Iannis Xenakis to compose works using found sound and a more constructive approach to music creation.

READ MOREEverything you need to know about: Musique concrète

Stockhausen and Boulez would also use principles of chance in composition, something also adopted by the likes of John Cage (who also famously flipped the whole experimental musique concrète philosophy on its head – or foundations – by releasing a recording of 4 minutes and 33 seconds of silence. Well, why not?).

Musique concrète would eventually embrace technology and be inspired by it, and its influence would seep into popular music by way of Frank Zappa, The Beatles and Pink Floyd, with the chance element also famously adopted and adapted by Brian Eno with his Oblique Strategies approach to composition.

Eno would go on to also take the concrète philosophy into some of his early albums like On Land, leading to the term ‘ambient music’, which, while having its roots very much in found sounds and atmospheres on these early albums, would eventually drift rather calmly and beautifully to create sub genres of chilled electronic music of its own.

On top of its musical influences, you can even argue that musique concrète goes much deeper, influencing much of the actual music technology that has sprung up since the 70s – many of the synthesis, DSP and sampling techniques owe a much bigger debt to the philosophy of musique concrète and its no-holds-barred approach to sound manipulation and processing.

To the music - the '60s!

In the very early 1960s, the true story of the synthesiser really starts in earnest. Paul Ketoff was an engineer at RCA, so knew a thing or two about synthesis from their early experiments. He designed an instrument called the Syn-Ket in 1962 for the American composer John Eaton. However, it was not commercially available – despite being used by Ennio Morricone for his film scores – and it would take two men, Don Buchla and Robert Moog, to bring the synth to the masses.

In the 1960s, electronic components were starting to become smaller and much more affordable, so no longer did you require an RCA-sized room to house a supercomputer capable of creating and manipulating sound. Electronic music might well have been only in its infancy in this decade, then, but it was just about to become mainstream, with a smattering of popular composers and one or two choice new synth instruments.

READ MOREThe 10 greatest synthesizers of all time: the machines that changed music

Buchla and Moog must take the credits here, and be lauded as the godfathers of the modern synth and the music itself. In the 1960s, they both separately developed voltage‑controlled modular synth systems that, while still expensive, did manage to come within reach of some of the big musical names of the time.

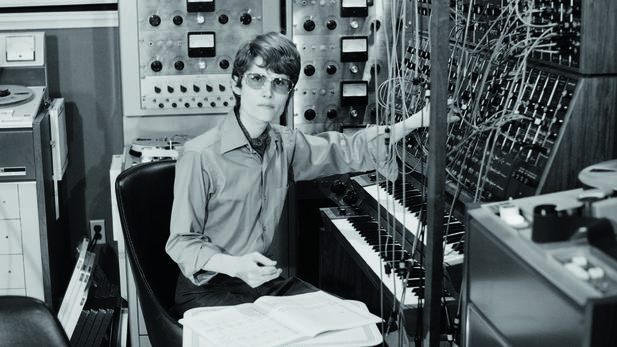

The Beatles, Frank Zappa and The Beach Boys all dabbled with early synthesisers, although perhaps the first pure and total electronic piece – an entire album’s worth, actually – came by way of Wendy Carlos, whose Switched-On Bach recreated pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach by way of one of Bob Moog’s modular synths. Now, we really were starting to rock the circuits in a big way.

In the late 60s, other artists were waking up to the idea of Moogs and Buchlas. Kraftwerk’s first lineup, known as Organisation, and other German pre-Kraut rock bands, were enjoying a more psychedelic phase but were now among the first people to adopt Moogs and would change the course of music history as we shifted into the 1970s.

Raymond Scott

Raymond Scott has been described as the ‘audio version of Andy Warhol’ yet has largely remained behind the scenes of electronic music history. He was a composer and technologist, and while he had his music licensed in cartoons, films and musicals, it’s perhaps his electronic research that is his biggest legacy.

He was one of the first people to come up with the idea of sequencing notes together, with a machine capable of producing tones. He invented the Electronium during the 60s, a device shrouded in mystery, but it was a combined synth and generative music producer – perhaps the first workstation,but almost certainly one of the first keyboard synths.

Scott and Bob Moog also worked together and the latter – now widely regarded as a godfather of synth music – cited Scott as one of his greatest influences. Google launched an excellent guide to electronic music last year that gives Scott the space he undoubtedly deserves in its history.

Progress to pop

Both in the UK and the States, rock was taking a more progressive turn and soon keyboard players like Keith Emerson, Rick Wakeman and Geoff Downs became early adopters of synths, although rather than create new electronic sounds, they preferred to emulate existing ones and play long – perhaps too long – solos with them.

Wendy Carlos was maintaining the more classic side of electronic music with the theme to the notorious 1971 Kubrick film A Clockwork Orange, but in 1974, Kraftwerk finally got their synths together to come up with one of the defining tracks, nay albums, of the genre.

Autobahn was its name and the title track was different on so many levels. It was almost entirely electronic – bar the odd flute and guitar – it also used vocoding, electronic percussion and, of course, synths, not to mention that it was more than 22 minutes long. Perhaps only electronic music as a genre could be heralded in with a covers album of Bach songs and a tune about a motorway, but as a musical force, it was here to stay.

Jean-Michel Jarre

Jean-Michel Jarre must have felt pretty alone in the 70s. While Emerson, Wakeman and Downs were playing synthesisers like be-cloaked keyboard wizards, and the ’League and Cabs were exploring the machines’ innards like scientists, Jarre just wanted to create pure synth music, with lush melodies, chords and memorable tunes; nothing too experimental, but nothing too noodly. He wanted to use early sequencing, and he wanted to be popular without the pop, and with the albumOxygene, he certainly got what he wished for.

INTERVEWJean-Michel Jarre: "I always considered stereo to be a fake process, created in the ‘30s, just to produce a sense of space"

This masterpiece recording, and theOxygene single (part IV), were his introduction into the big league. Recorded with, among other classics, a VCS3, ARP 2600, Eminent 310 and Korg Mini Pops in Jarre’s kitchen(!) it stands up as one of the defining albums in electronic music, yet really exists in a sole category marked ‘Jarre’. There’s Vangelis’ and Wendy Carlos’ soundtracks, yes, and there’s popular synth music, but then there’s the enigmatic French composer stuck somewhere in between. Or, indeed, everywhere else.

He now straddles soundtracks and EDM (see his much later collaborations), he still has hit records, he can play to millions of people in ridiculously huge open-air concerts. He uses a ‘laser harp’ ferchristsake!

Yes Jean-Michel Jarre, with his adoption of every technology, old, new and possibly not even invented, and his ability to dabble in just about every electronic genre is, very probably, the ultimate synth musician. He is out of place in time, both physically and musically, but he certainly deserves his own chapter (or at the very least, this box for now) in the history of electronic music. Actually all music, come to that. A true synth music legend.

Born in the UK

As the 70s progressed, the UK started to play an increasingly important role in the development of synth music. Kraftwerk had laid down the gauntlet in Germany, for sure, but Brian Eno was already sneering at his fellow progressive rock keyboardists, experimenting with synths and creating found-sound textures in the studio.

He was whacky, glam, serious and ‘out there’, and he would take Roxy Music into the charts, Bowie down oblique and electronic pathways with his Berlin trio of albums, and invent ambient music as we know it, and all in the space of just a few years in this decade.

CLASSIC INTERVIEWClassic interview - Brian Eno: “I use the DX7 because I understand it. I know that there are theoretically better synths, but I don’t know how to use them”

Meanwhile, a little-known fact in electronic music history is that part of its major development in the 70s was not because of the advances in synth tech nor the outlandish creativity of its players, but actually down to the formation of a youth workshop in Sheffield called Meatwhistle.

Here, not one but four influential bands (eventually) came together. Local Sheffield youths with a more creative vision were encouraged in just about every aspect of music and performance, inspiring one another and resulting in – to a greater or lesser extent – the formation of Clock DVA, Cabaret Voltaire, The Human League and Heaven 17.

The first two early League albums are now seen as two electronic masterpieces, produced by a cold dystopian version of the band that would later rule the pop charts in the 80s, but whose late 70s influence would certainly reach other artists, if not so much the record-buying public.

The Cabs, meanwhile, were Sheffield’s punk electronic act, putting the steel in Sheffield and, along with Clock DVA, are now seen as not only influential but laying the groundwork for major electronic labels that would come later, including Sheffield’s own mighty Warp Records.

The Mk1 version of Ultravox! were also early adopters of the synth in the 70s, notably an ARP Odyssey, one of the classic machines of that decade. This John Foxx-led brigade of art-house students shifted from Roxy glam to rock electronica over the space of three albums and a short space of time, but it was long enough not only to propel Foxx into a solo career that would produce one of the finest pure electronic albums of all time (Metamatic) but also influence a certain Gary Webb. And it was this young man who, at the end of the decade, would take electronic music out of the theatre workshop, and onto the theatre stage.

It's popular!

Gary, now Numan, was a punk rocker in his formative years, but in easily a moment that is up there in electronic music history with Kraftwerk driving on a motorway for the first time, he went into a studio one day to record a punk guitar album, found a Moog synth already switched on, pressed a note and was so moved that he ditched all the guitars on his next album and replaced them with synths.

Which, as they say, was nice. After he released the track Are ‘Friends’ Electric? we suddenly had synth pop as a genre, with everyone shocked into action – not least Numan himself – by this new force in music.

Up until then, music that used synthesisers was novel (see Hot Butter’s Pop Corn), soundtrack-y (see Wendy Carlos), novel and soundtrack-y (see Jean-Michel Jarre) or Kraftwerk (see Kraftwerk). Now it was popular, very popular, and it was British. Mostly. It had catchy melodies, it had vocals, it had songs. It was pop. Synth pop!

The pop years

Numan’s bowling ball of a synth song, Are ‘Friends’ Electric? would usher in the decade of synth pop, but while he took the glory, other synth bands were spitting blood. Liverpool’s OMD were already producing amazing synth tunes, using crappy, cheap keyboards and a drum machine called Winston.

As jealous of Numan as they have admitted they were, his success opened the door to a string of hit singles for them and many others, and they, in turn, influenced another electronic music icon, who deserves not one, but possibly three chapters in EM history.

Vince Clarke would hear early OMD B-Sides and realise that synths were the way to go for his formative compositions, and 40 years on, he’s still amassing the machines to make them.

In those four decades, he managed to form Depeche Mode, Yazoo and Erasure, and managed to have the odd hit record with all three of them. Vince is probably the most iconic writer of synth pop we will ever know (Just Can’t Get Enough, Love To Hate You, Sometimes and Only You earn him that accolade alone), yet is also the most unassuming.

And after launching the good ship Depeche Mode, he slipped across the gangplank before its voyage really began, leaving the captaincy (OK, we’ll leave that analogy now) to Martin Gore. And where Vince can claim the top pop honours, Gore can certainly claim the, well, gore. His more doom-laden, yet massively uplifting blend of songwriting has kept Depeche on top of the world for four decades now. Is there an electronic band more successful?

Yet while we can blame Numan, the Human League, OMD, Clarke, Foxx and Jarre for bringing the sound of the synthesiser to the masses, we should also give some credit to the manufacturers of the machines, for if it hadn’t been for the dramatic reduction in gear pricing over the late 70s and 80s, this decade of synth pop would not have been.

The big three Japanese players of Roland, Yamaha and Korg moved in to steal some of the thunder from the mostly American players like Sequential, Oberheim, Moog and ARP; their machines rocked at rock-bottom prices, simple as that. Synths from the Roland Juno and Jupiter, Korg MS, Mono and Poly ranges all made their mark, but it was Yamaha’s CS-80 that became the first synth to define a soundtrack or two.

Built in the 70s, yes, this synth was used extensively by Greek composer Vangelis and soundtracked some little known film about running – Chariots of Fire – but, more importantly (for geeks like us), soundtrack an era- and genre-defining sci-fi film. Blade Runner took many years to fulfil its destiny, and through many different versions, but they all shared Vangelis’ incredibly mesmerising soundtrack, which would not have been possible without this monster polysynth from Yamaha.

READ MORE10 of the most incredible synth film soundtracks from Hollywood history

As popular as Vangelis’ work was, it wasn’t really the pop that made synth pop though, and for that we can thank everyone from Blancmange to Pet Shop Boys, Eurythmics to the Human League Mk2, a-ha to Soft Cell, Buggles to New Order and many (many) more. Synth pop was massive, but only really for a relatively short time before the technology changed the sound and people’s tastes moved away from its lush analogue roots towards a more digital sheen.

Synth pop lost the analogue lustre and the 80s gave way to pomp, rock, SAW and dark times. Yes, the all-new digital synths, again from the big players, sold by the million – Korg’s M1, Yamaha’s DX7 and Roland’s D-50 shifted record numbers – but they were largely used to replicate ‘real’ sounds rather than those of electronic music’s analogue heyday.

It would eventually take an entirely different set of circumstances to really bring electronic music back to the fore. And it would be an all-new version, and vision…

Electronic dance music

It’s a term now looked upon with horror in some dance music circles, but the original ‘electronic dance music’, those oft-illegal repetitive beats that started off in the mid-to-late 80s, were the saviour of the electronic sound.

Like many movements, and indeed like our history of the synth music machines above, there are many wild stories as to its origins, but you can safely say that, while Kraftwerk had some involvement, dance music’s origins – like rock ‘n’ roll before it – were most definitely Black and US-based.

New York disco, Chicago house, hip-hop and Detroit techno were the catch-all labels and artists like Afrika Bambaataa (hip-hop), Frankie Knuckles, Farley ‘Jackmaster’ Funk, DJ Jesse Saunders and Marshall Jefferson (house), Phuture and Sleezy D (Acid house), Juan Atkins, Derrick May, Kevin Saunderson (techno) and many more all deserve mighty pedestals.

READ MORE40 years of techno: how synths and drum machines have defined a genre

As do instruments like the Roland TB-303 Bass Line and TR-808 and 909 drum machines. Roland didn’t make these instruments for dance, it must be stressed – the 303 came out well before dance in 1983, designed as a bass accompaniment machine – but the artists above, and so many more, found these cheap, second-hand drum machines and synthesisers and abused them into a new and world-defining genre (and many, many sub genres).

The electronic beats and squeals provided by the Roland gear were a unique force. Bands like New Order and Pet Shop Boys brought dance sounds from the States to Europe and the mainstream, and combined with – it must also be noted – the drugs of the time, helped dance music spread from the suburbs of the US cities to Ibiza, Manchester, Sheffield, London, Berlin and beyond. The 90s became the decade that started a million new dance genres, not to mention a million often unlikely producers.

Amazing '90s electronic music

The 90s was great for electronic dance music, of course, but there was also another movement of down-tempo trip-hop that might not have always been as electronic in nature – samples came from everywhere – but its DIY ethos certainly took it cues from electronica. As well as the more obvious protagonists – check out anything from Massive Attack – you can find amazing productions by artists including DJ Shadow, Air, Björk, Howie B, Laika, Lamb and many more.

On a more electronic tip, pretty much anything by Underworld, Orbital, Pentatonik, Plaid, Moby, The Chemical Brothers and LFO from this decade is worth tracking down, and Aphex Twin was in his most prolific mood, redefining ambient, jungle and anything in between. We’ve also mentioned Warp Records: just check out their Artificial Intelligence compilation – that features everyone from Autechre to The Orb’s Alex Patterson – for a beautiful slice of 90s underground life.

Faceless techno

In a slight variation of the classic phrase, ‘if you can remember the 60s, you weren’t there’, it could be said that ‘if you kept abreast of all the dance genres that the 90s and 2000s produced, you are probably a superhuman’. By BPM, dance music went from dub to D&B, trip-hop to happy hardcore.

Nothing was out of bounds, the more outrageous or faster the bpm, the better. There were stars and mainstream hits – stand up Orbital, Prodigy, Leftfield and Massive Attack – but of the vast majority of DIY producers, of which there were thousands producing music relatively cheaply, most were faceless and disappeared as quickly as it took to produce a track, press and sell 1,000 white labels.

There were pointless debates over which was best – we’re jungle purists, obviously – and eventually dance music would have to evolve, and some would saydissolve into something altogether new. It shifted uncomfortably under its own weight – and of course, the money being made. Superstar DJs were born and lived in private jets and to this day, they raise their hands and tweak a volume knob in front of tens of thousands… and cash the cheque.

READ MORE7 artists shaping the future of electronic music

The big roadblock, ironically, was selling electronic music back to the States so ‘electronica’ and ‘EDM’ became the new catch-all phrases. The new stars were the likes of David Guetta, Skrillex, Calvin Harris, Tiësto and deadmau5. The sound became massive, full of dubstep wobbles and bassline, well, bass.

And the synths became harder… and softer. The appropriately-named Massive, along with Serum, became the most widely used synths in EM production, both made in software, but both as big-sounding as anything made with real electronic components.

The 21st century

Our history concentrates on some of the main directions that electronic music took this century like dance music and EDM, but many other artists also deserve a mention and there are, of course, many more underground acts to search for.

And electronic music in this century really does, as you might expect, cover every spectrum of music, from the more pop leanings of The Killers, Future Islands and Chvrches to experimental composers like Jenny Hval, Boards of Canada and (at one time anyway) M83.

Then there are the once electronic producers who have broken through the ranks to the mainstream: Jon Hopkins is still widely regarded for his extremely dynamic electronic works, while also dabbling in tunes with Eno and Coldplay, while William Orbit went from Strange Cargo electronics to awards with Madonna – quite a journey in any electronic musician’s book.

INTERVIEWJon Hopkins: "I don’t really have any modular synths, drum machines or any of that stuff - it’s all really Ableton and source audio from random places"

Then are also many acts who have rejoined the dots and bought the electronic sound up to date while unashamedly nodding to its past. Will Gregory and Goldfrapp certainly helped bring back the ‘analogue’ in synth, LCD Soundsystem and Daft Punk took elements of everything electronic and simply made them cool, while Ulrich Schnauss occasionally nodded back to Tangerine Dream before actually becoming Tangerine Dream.

Finally, more than two billion Spotify streams can’t be wrong. The Weeknd’s Blinding Lights is probably the most high-profile synth pop tune of the last couple of years, having been number one the world over and shifting as many copies as any synth song. It wears its 80s roots well – those riffs could have come from any a-ha or OMD single – and proves that electronic music, in its purest form, is alive, well and as popular as ever.

So where are we now?

The 21st century hasn’t all been about big basses and EDM, but keeping abreast of any music now, especially within a genre so wide as electronic music, is both hopeless and massively hopeful; there is both too much and something for everyone.

You can, should you wish, track down any genre – from electronic goth rock to ambient dub ‘n’ bass, chiptune techno to modular synth pop – on any of the many streaming services out there (OK, we haven’t tried those, but you get the point).

Electronic and synthesised music is now used everywhere: from slabs of pure pop joy (The Weeknd anyone?) to searing soundtracks, from retro themes (Stranger Things, obviously) to experimental soundscapes in video games, and from post-rock to generic rock and pop. In fact, you could argue with the latter genres that all music is synthetic these days – it’s generally artificially created within computers, after all, but let’s not open that particular can of worms.

And all these kinds of music exist because any producer can put their music out in this DIY environment. We have countless tools at our disposal to create music – there’s a whole chapter to be written on Eurorack synths, for example – and it's easier than ever to do. You can get a complete recording studio on a Mac, PC, tablet or even a phone; music can be made literally anywhere, and released on just about anything.

But the joys of releasing your own music, without the constraints of needing a record deal anymore, are tempered by the fact that, ironically, there are fewer big record companies and traditional media outlets filtering the vast – and we mean vast – amount of music out there. It’s a sea of noise, but it is also one you can navigate.

Electronic music and the synthesiser’s histories are as complex as the definition of the genres that they have produced, but that’s also their beauty and appeal. The search is as amazing as the discovery, with more artists, yourself included, using synths and creating and distributing music on platforms, to a wider audience than ever before.