Last week in Japan, Formula 1’s 10 team bosses held an impromptu meeting, saliently without inviting Formula One Management or FIA representatives.

Advert | Become a Supporter & go ad-free

It is, of course, their right to meet wherever or whenever they choose. But, tellingly, the meeting marked their first since Liberty Media acquired FOM two years ago and, by many accounts, it was the first such meeting since the Formula One Teams Association disbanded back in 2014.The convener, believed to be Mercedes (various sources told RaceFans that Mercedes Motorsport CEO Toto Wolff called it) attempted to keep the meeting secret, going as far as requesting that attendees enter via the ‘tradesmen’s entrance’ at the rear of the team’s hospitality unit. One team boss refused to comment on the basis that “I gave my word in the meeting not to talk to the media”.

According to one source willing to discuss the meeting, the subject was ‘How to improve (spice up) the show,’ while another said that the recent drop in income (derived from a combination of TV revenues/race hosting fees and ‘others’ – predominantly hospitality sales and ‘bridge and board’ advertising) and dwindling eyeballs had been a “wake-up call for us all”.

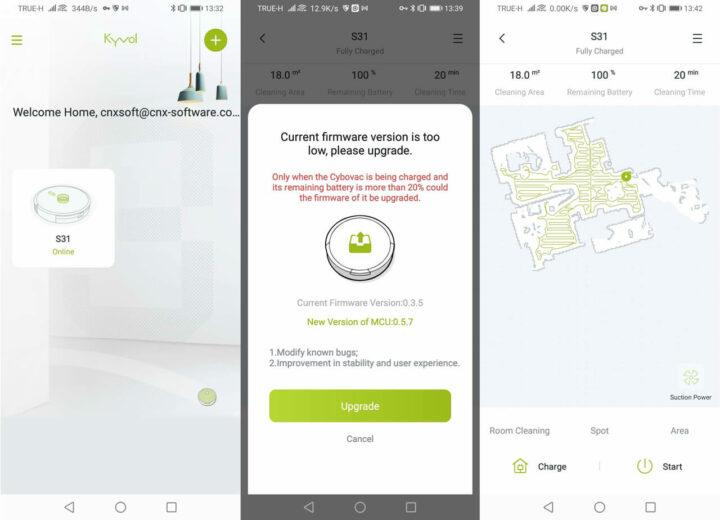

Indeed, despite (or because of) massively ramped-up marketing spend, a new logo, a snazzy app (which infuriated die-hard fans) and an internet streaming service claimed by Liberty to be the most sophisticated in world sport, the team are due to share around 4% less for the third quarter of 2018 – a continuing trend.

TV ratings are down too. Not only that, but the total hours of F1 broadcast has fallen by around a quarter year-on-year over the first 10 rounds, from 23,000 to 18,500, due to the losses of Sky Germany/Austria and F1 Latin America.

A worrying (but as yet unconfirmed) year-on-year comparison for the Russian Grand Prix indicates a TV ratings slump of over 20 per cent versus last year. Liberty is said to put this down to a later slot in the year, yet going into Sochi the championship fight between Lewis Hamilton and Sebastian Vettel was much closer than now, so that does not stack up.

The latest Nielsen Sports broadcast report, shared with RaceFans by vice-president for global motorsport Nigel Geach, shows a one per cent cumulative year-on-year decline in TV audiences over the first 10 rounds, despite audiences being up (on 2014) for events that clashed with the FIFA World Cup. True, one per cent is no great shakes – but Liberty is a media company first and foremost, and as such on a mission to grow the sport.

The faltering launch of F1 TV Pro remains a cause for concern as well. Speaking at a recent Vanity Fair summit, F1 CEO Chase Carey admitted that F1’s much-vaunted OTT streaming service had “more glitches than we hoped for,” adding, “For us, it’s early days…”

All this is cause for concern. Hence that meeting. Not to be outdone, Liberty called a follow-up on Sunday where the same topics were (allegedly) discussed.

But talk of the upcoming Brazilian Grand Prix brought more bad news: the teams will not be paid (albeit indirectly, given F1’s income is distributed from a “pot” after deductions made for Liberty’s expenses) for this year’s Brazilian Grand Prix.

Or next year’s round.

Or the 2020 race.

Apparently the race agreement consisted of two parts: a hosting contract with the promoter, known to be a long-standing associate of ex-F1 tsar Bernie Ecclestone, whose wife was once marketing director for the company; and a separate financial underwriting agreement with Sao Paulo city/state. Thus public coffers paid the hosting fee, with the gate covering promoter costs (and profits).

It seems that during Bernie’s last days in office he extended the promoter agreement, but failed – conveniently forgot? – to obtain the necessary fiscal agreement. The promoter maintains he has a valid deal and, if F1 failed to sort the funding, that’s not his problem, so the teams (and FOM) are travelling all the way to Brazil and staging the show for three straight years without earning a (coffee) bean for their efforts.

Asked to comment, an insider said, “That’s the short version, but you’re not far off the truth,” adding, “We were all surprised when we saw the contract, but Mr E was the boss at the time…” Somehow one can’t imagine Ecclestone taking his show 6000 miles across the Pacific Ocean without payment, yet Liberty seems willing to do so.

Advert | Become a RaceFans supporter and go ad-free

Against this background, is it any wonder that the teams are getting increasingly jittery about F1 under Liberty? Already the word is that the likes of Wolff, Renault’s Cyril Abiteboul and Christian Horner (Red Bull) are pushing for fewer races – or increased revenues and less stringent budget caps for more than 20 races – all of which puts Liberty under even greater pressure to grow F1.

Is it within Liberty’s power to achieve its stated objective or are outside influences conspiring against its ambitions? Expressed differently, has interest in global motorsport peaked: have we seen ‘Peak F1′?

Formula 1 is not alone in experiencing downturns in interest: NASCAR and IndyCar – both homegrown in the Land of the Automobile, remember – face dwindling attendances and TV ratings, with first-named suffering drops of between 20 and 30 per cent for some races, with FOX Sports’ viewership being 29 per cent down on 2016.

Worse, the average age of viewers has shot up nine years to 58 in just 12 years – the third-oldest bracket behind golf and tennis – indicating that the series is failing to attract young blood. Millennials are not acquiring their parents’ taste for motorsport. Sitting on bleacher stands at an oval is as uncool as drinking alcohol.

The same goes for watching TV, where Netflix also trumps NASCAR and the like. Thus sponsors are walking and, where replacements are found, their funding levels are well down. When sponsors such as supermarket group Target walk away from Chip Ganassi’s IndyCar team after 27 years or DIY chain Lowes exits Hendrick Motorsport and its seven-time champion after 17 seasons, something is surely worryingly amiss.

Just as folk talk about Peak Car – particularly in cities serviced by the likes of Uber – so talk is now of Peak Licence. US statistics indicate just how Future Kid is shying away from motor cars and, by extension, motorsport: In 1983, 46 per cent of American 16-year-olds held drivers licenses; thirty years on that figure had halved, and continues to fall. So does the average annual distance travelled.

True, not all license holders are petrol-heads, not vice-versa, but as a benchmark it is telling, for it points to falling interest in matters motoring, and, therefore motorsport. Equally, if there is no correlation, then motorsport is being hit by a set of unhappy but proportionate coincidences…

A paper published by phys.org in January found worrying similarities in the United Kingdom: Drivers’ licenses amongst 17-20-year-olds peaked at 48 per cent in 1992/4 and 75 per cent for 21-29-year-olds, dropping to 29 per cent and 63 per cent respectively two decades later. In 2010-14, only 37 per cent of 17-29-year-olds reported driving a car during a typical week, whilst the equivalent figure was 46 per cent in 1995-99.

Now consider how all this relates to F1. While the slide in TV ratings over the past six or so years can be (partly) explained by F1’s switch to pay-TV, the fact that folk refuse to pay for F1 broadcasts is a worrying trend. This points to convenience customers rather than die-hard fans of the type Liberty professes to target; equally, there is a correlation between the rise in pay-TV and drop-off in sponsor interest.

Internet shopping, budget airlines, virtual socialising, taxi apps and other connected activities all mean that the car is no longer the necessity it once was, and, as interest in the car wanes, so F1 gets affected. Add in that Millennials are more likely to think “electric green” than V8 or even hybrid, is it any wonder that motor manufacturers are flocking towards Formula E?

Where in the mid-noughties F1 boasted seven motor manufacturers each spending hundreds of millions (dollars) per annum, today the sport has but three-and-half (Honda being an engine supplier only), while Formula E has eight spending around a tenth that. Note the shift?

Motor manufacturers have traditionally funded motorsport activities via a combination of R&D spend and marketing budget – with the mix varying from company to company, That being so, on the sporting front they now face two diametrically opposite choices: fossil fuel and electric. It stands to reason that budgets of participating brands are split, reducing the amount available for F1 spend, or even blocking an F1 entry.

Advert | Become a RaceFans supporter and go ad-free

With car companies devoting increasing time and effort to autonomous car development, so both budget centres will come under renewed pressures through being required to contribute, further decreasing the amount available for motorsport of whatever persuasion. Spot the spiral?

Where once F1’s calling cards bore the messages ‘Win on Sunday, sell on Monday’ and ‘Racing improves the breed’, so far removed are F1 cars – and the racing – from the real world that such slogans no longer ring true. If anything, Formula E’s technology, including treaded tyres and energy storage, holds greater road relevance than anything F1 currently offers – at a tenth of the price.

Consider that the Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi alliance recently overtook VW Group for the number one motor manufacturer spot despite having only recently re-entered F1 (without much current success, it must be added), while Nissan faces its maiden FE season. Consider, then, that both are market leaders in their segments electric car segments, whilst Mitsubishi is a plug-in hybrid leader.

Apart from newly-resurrected Alpine they don’t have a true performance brand between them, with sub-brands such as Dacia, Lada and Datsun, with zero motorsport pretensions, providing volume.Yet, performance brands such as Audi, Porsche and BMW steer clear of F1 – but have signed up to FE…

Here’s another pointer: For the past three years F1’s pre-season testing in Barcelona has clashed with Mobile World Congress, held in the city’s Fira halls. Over eight days of testing the circuit considers itself fortunate if total attendance hits ten thousand – despite free entry to anyone holding a race weekend pass. Yet the simultaneous MWC regularly draws 100,000 geeks: guess where the future buying power lies?

Ditto the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, which annually attracts as many visitors as does the Indianapolis 500, which brands itself as the world’s largest single-day sporting event. Tellingly, brands such as VW and Renault now spend more on their CES exhibits than they do at mainstream motor shows, which have gradually lost their lustre. Indeed, VW, Ferrari and Fiat etc., shunned the Paris Motor Show earlier this month.

All this points to rapidly shifting landscapes for motoring and motorsport in general, and F1 in particular. The pressures F1 faces are fundamentally external and not of its own making, yet they are very real pressures and the challenge is for the sport (and Liberty) to adapt faster than the landscape shifts. As always in F1, if you’re not moving on fast forward, you’re going backwards.

If F1 (and the likes of NASCAR and IndyCar) fails to adapt it will fade into irrelevance before dying a slow death. Liberty and the teams need to do more than simply “spice the show” – they need to reinvent the sport totally, from format through technology and governance to fan experience and broadcasting. All that takes massive commitment; above all, it requires not impromptu gatherings, but enormous will from all concerned.

The dinosaur lacked that crucial characteristic…

Follow Dieter on Twitter: @RacingLines

Go ad-free for just £1 per month

>> Find out more and sign up